Why mathematics is crucial in the Global Gender Gap Report?

Article by Elisabetta Strickland

The Global Gender Gap Report was first published in 2006 by the World Economic Forum: the 2020 edition of this international gathering that was held in Davos before the SARS-CoV2 attacked the world, covered 153 countries and the Global Gender Gap Index, which is one of the interesting outputs of the report, is designed to measure gender equality, precisely to measure gender based gaps in access to resources and opportunities in countries.

It is not necessarily true that highly developed countries should have higher scores. The progress towards gender parity is benchmarked in four dimensions: economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, political empowerment.

In addition the report examined prospects in the professions of the future, presenting a decidedly mixed picture. Overall, the quest towards gender parity has improved: greater political representation for women has contributed to this, even if overall the political arena remains the worst-performing dimension. Drilling down into facts and figures, none of us will see gender parity in our lifetimes, and nor likely will many of our children.

The report highlights three primary reasons for this: women have greater representation in roles that are being automated; not enough women are entering professions where wage growth is the most pronounced (most, but not exclusively, in the STEM area, i.e. Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics), and women face the perennial problem of insufficient care infrastructure and access to capital.

What appears absolutely clear is that educational attainment gaps are relatively small on average but there are still countries where investment in women’s talent is insufficient: ten percent of girls aged 15-24 in the world are illiterate. Further, in these countries, education attainment is low for both girls and boys, which calls for greater investment to develop human capital in general. Even in countries where education attainment is relatively high, women’s skills are not always in line with those required to succeed in professions of the future.

Moreover, comparing where women are currently employed with the skills they possess, it turns out that there are some occupations where women are under-utilized even if they have the needed skills. Women could further contribute to many of them, including some high-tech roles, if current barriers could be addressed.

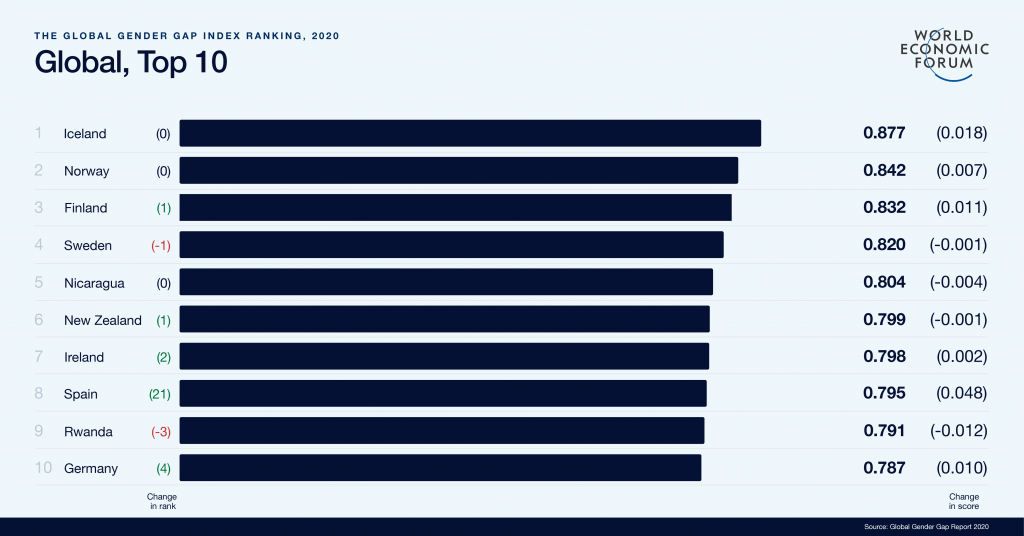

Looking to the future, the report reveals that the greatest challenge preventing the economic gender gap from closing is women’s under-representation in emerging roles: in cloud computing, for example, just 12% of professionals are women. Similarly, in engineering and data, the numbers are 15% and 26% respectively. The top country for gender parity remains Iceland, for the 11th year running. The top ten countries have been, after Iceland, Norway, Finland, Sweden, Nicaragua, New Zealand, Ireland, Spain, Rwanda, Germany. The most improved countries were Albania, Ethiopia, Mali, Mexico and Spain.

It has been pointed out among the main facts that, while gender parity efforts have focused on the supply side of future skills for girls and women, there have been few demand side efforts to create incentives for women and girls to enrol in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) education programs or to create an accelerated pathway for women to be hired into the highest-growth roles of the future, particularly those applying STEM skills.

As labor markets go through a period of intense change, there is a unique opportunity to embed parity into the future by balancing efforts between the demand side of growing jobs and the supply side of future-ready skills.

The Global Gender Gap Report provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of the global gender gap and of efforts and insights to close it. The index offers a benchmarking tool to track progress and to reveal best practices across countries and subjects.

In 2020 the report found that the gender gap has closed slightly since the year before, yet it will take 99,5 years to achieve full parity at the current pace! The report highlights the message to policy-makers that countries that want to remain competitive and inclusive will need to make gender equality a critical part of their nation’s human capital development. In particular, public-private cooperation within countries will be a critical element for closing the gender gap.

Text comment...

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.