Drawing the beauty of mathematics: an interview with Constanza Rojas-Molina

Interview by Francesca Arici and Anna Maria Cherubini

- Born inChile

- Studied inFrance

- Lives inGermany

Interview

Constanza Rojas-Molina is a Junior Professor in the Stochastic Group at Düsseldorf University working in mathematical physics and passionate about science communication. Her technique of choice are illustrations. She has been a reporter for the Heidelberg Laureate Forum and one of the creators of the drawing challenges #noethember and #mathyear.

How would you explain your research to a non-specialist?

Whenever I explain my topic I try to avoid the technical details and keep the physical picture, which is much easier to describe! I work in mathematical physics, in particular, I study a model from condensed matter physics, and I consider the propagation of electrons in materials.

Electrons in materials can either propagate or not, and depending on the scenario, one says that the material is either a conductor or an insulator. The physicist P.W. Anderson discovered that when the material has impurities it becomes an insulator solely as an effect of those impurities. This phenomenon is called Anderson localization and can be modelled using randomness. The mathematical setting is that of Schroedinger operators with a random potential. In more technical terms, I study the spectral theory of random Schroedinger operators. I focus on a class of quasi-crystals with impurities. There is a lack of translation-invariance that makes things more complicated but the effect of the impurities is in general pretty strong so one tends to always observe an insulating phase.

The questions that we are interested in are the asymptotics in time of the solutions. Do these functions escape at infinity or are they localised in a region of space for all times? The mathematics involves a lot of techniques from different fields: analysis, probability, dynamical systems… I like this subject!

When did you decide to become a mathematician, and why?

That was pretty late in my career! I actually started with physics: I thought I was going to do astronomy because I come from a region in Chile where there are several astronomical observatories and when I was younger I thought I would pursue that career. Later I realized that it was hard for me to understand the physics without the maths, and that’s what lead me to switch careers. By attending courses in advanced mathematics I realized how pretty the subject was, and I started finding beauty in proofs. Even if I would fail a test, I would see the corrections and be amazed at how beautiful everything was, how nicely it all fits together. This is how I discovered I had a taste for mathematics.

When I was in high school I was a good student and mathematics was something that came easily to me. I studied it because it was useful and one needed it, but I didn’t think of having a career in mathematics because I didn’t know what mathematicians do. I only knew about mathematics teachers, and my maths lessons were not particularly stimulating. On the other hand, my chemistry and physics teachers were very good and compensated for that. I think it was during chemistry and physics class that I found this love for quantum phenomena. So this happened pretty late, and one thing led to the other.

You moved from Chile to France and Germany, passing through Slovenia (did I miss anything?) Can you tell us something about your story?

I got my bachelor in mathematics after initially starting with physics. As an astronomer, I could have had a very good job with a good salary, but I didn’t know what I could do with a degree in mathematics except for being a teacher. What I actually had in mind was to get a degree in maths and then go back to physics. But then I ended up liking mathematics so much that I enrolled in the master program at my hometown university.

I kept being interested in physics, thinking that I may go back to that degree later. But at the same time, I wanted to move away and do a master’s abroad, in Europe: I really wanted to go to France.

Nobody at my home university helped me pick the place. I had internet and I did all the searching on my own. I applied to several places and some rejected me, but I was admitted to the Master’s programme at the University Paris 6, in France.

I went to my mother and told her I wanted to do a master abroad, since she was supporting my studies back then […] I thought she was going to talk me down, so I had prepared a back-up plan: studying mathematical engineering in Santiago del Chile. Despite my worries, my mother was very supportive.

I went to my mother and told her I wanted to do a master abroad, since she was supporting my studies back then (in Chile, even though universities are public, they are autonomous which means students – and often their families- have to pay very large sums in fees). I thought she was going to talk me down, so I had prepared a back-up plan: studying mathematical engineering in Santiago del Chile. Despite my worries, my mother was very supportive. She thought it would be a good experience, so I went to Paris without knowing anyone, with only my family’s support. I actually thought it would be only for one year, but then I found a topic that I liked and wanted to pursue my studies, so I ended up staying.

I wrote my master thesis with François Germinet, who later became my supervisor. I found out that I really liked the topic of random Schroedinger operators, because of the quantum physics background.

After my Master’s I applied for a grant from the Chilean government to do my PhD and I got it. This covered my salary for four years, while I lived in Paris.

It was in France that I met my husband, who was there finishing his PhD in maths applied in astrophysics. By the time I was finishing my PhD, he was in Slovenia doing a postdoc. At that time I applied for a Marie Skłodowska Curie postdoctoral fellowship to move to Munich and work with Peter Müller, who was a collaborator of my advisor and whom I had met during my PhD. I was awarded the MSC fellowship but I postponed it as much as I could to be in Slovenia with my husband. The institute where he was working, and his director, Marko Robnik, welcomed me as a guest. They gave me office space and invited me to participate in their activities. This allowed me to be with my husband, spent some time at home, have some family time. I really needed that and I’m grateful to Peter for his understanding and patience and to Marko for welcoming me into their group.

After that, I went to Munich and my husband got a postdoc in Germany as well, in Nordrhein-Westfalen. After Munich, I went to Bonn, I was there for two years and a half, working with Anton Bovier and Margherita Disertori, and now I am in Düsseldorf as Junior-Professor. My husband and I are finally living together after so many years! All this time, we were always trying to follow each other’s steps.

How did your project, the Rage of the Blackboard, start?

This started during my MSC Fellowship in Munich. I had always wanted to do outreach, but I didn’t speak German, so I couldn’t go to schools, so I thought that I had to do something in English. I was writing my MSC proposal around the time of the EU campaign “Science is a Girls’ thing”, which unfortunately did not depict the true face of science and was met with criticism. I realised that most people around us have no clue about what we researchers do and experience.

So I decided I wanted to interview female mathematicians with permanent positions and ask them how it really was to be a woman in science, and how they had gotten where they were. I wanted to ask them about real life as a scientist, even about moments of frustration, failures, difficulties. We tend to forget that failure is part of the process, and nobody talks about it. The interviews with scientists were the biggest part of my project, but not exclusively: by opening a blog I wanted to create a platform to explore ways of communicating sciences.

What is the biggest challenge you face in science communication?

In the beginning, the biggest challenge was finding people to interview. The senior female researchers I had around did not want to give me interviews. Maybe they didn’t have time, or they felt it was too much responsibility to be seen as role models. Sometimes I have the impression they felt intimidated. Sometimes I didn’t get a reason why.

It was through the EWM network that I got to interview Anna Dall’Acqua, who prompted me to talk to Sylvie Paycha, and Susanna Terracini. They were incredibly generous with their time and patience, and they trusted me, even though I had no experience running interviews or blogging!

I found women involved in women in science initiatives, and these were the ones who were willing to talk to me and suggest new people to interview. It was through the EWM network that I got to interview Anna Dall’Acqua, who prompted me to talk to Sylvie Paycha, and Susanna Terracini. They were incredibly generous with their time and patience, and they trusted me, even though I had no experience running interviews or blogging! These first interviews helped me get started and to have something to show to attract other interviewees.

The other thing is that for a long time I used a pseudonym (E.A. Casanova, taken from my grandmother’s name) because I felt that my colleagues were seeing my involvement in outreach as a distraction from my research. I had to do outreach because it was part of my MC, so I had a good excuse. I actually was awarded a Humboldt Fellowship at the same time, and I picked the MC because it “forced me” to do some outreach. I wanted to give something back, to have an impact besides the few people that were going to read my papers. I was very serious about it and I was careful, and I did it with a lot of dedication. That’s why it was hard to see that my colleagues were not taking it seriously.

In the job description, there is always the requirement of outreach, but the truth is that, once you are in the system, very often there is no support for researchers that want to do outreach. Everything in my blog was done on weekends, evenings and holidays. I am talking from the perspective of a scientist that wants to do science communication, but the truth is that often I am either a science communicator, or a researcher, but not both. The mix is not really recognised in academia. This drawback won’t stop me from doing outreach, but honestly, I think that the only way I can do it is because I have no children, nor relatives that I have to take care of, and my husband is very understanding and supportive. I’m lucky to have a lot of support at home to do it.

How would you describe your experience at the Heidelberg Laureate Forum in the past couple of years?

I went to the HLF in 2018 for my 3rd time. The first time I went as a postdoc, but I enjoyed it much more the 2nd time, when, for the first time, I went as part of the Blogging Team. Covering the HLF is probably my dream job: I get to attend lectures, do graphic recording, learn about research in other areas (for instance machine learning) and hang out with the very interesting people in the press room. I learnt a lot from all that.

The HLF was a great experience, it made me feel I was REALLY doing science communication. In some sense, this was the first time that someone acknowledged me as such: the people from the organization and the press team, in particular Tobias Meier and Wylder Green, recognised me as a blogger. I am very fond of this place and their team!

Your illustration techniques have evolved over time, and now you also do graphic-recording. Have you ever tried recording a maths lecture?

Oh, that’s hard. I recorded mathematician Eugenia Cheng talking about her career, but I have never covered a real math talk. I did, however, draw a graphic summary of the It all adds up event in Oxford, but that was not live. I took notes during the lectures, then I did drawings at home. It took me a while to get the pictures right.

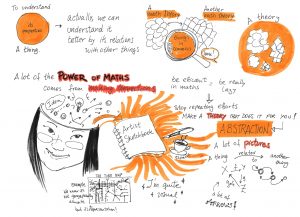

The Heidelberg Laureate Forum has a different style. The mathematics talks are not that technical, and there are also a lot of computer science talks. Computer science is somehow easier to draw. That said, maths is a very visual language, mathematicians use a lot of pictures and very often they need to draw in order to explain their ideas. I have not tried to record maths talks, but if I did I would have to learn about the topic beforehand.

Graphic recording combines everything I like and it uses a lot of symbols. After all, we mathematicians do the same: if we need to explain a concept, we very often go to the blackboard and draw! In order to do graphic recording, you don’t need to draw well, but to convey a message. It’s language to write down ideas: in graphic recording, the language is made of icons and sketches, and I think this is very similar to maths language with its formulas and graphs.

Can you tell us more about your Noethember project with Aperiodical?

A few years ago I took part in #inktober, and it was a very nice experience. This year, due to the start of the semester and other commitments, I could not take part in it, so I promised to do something for the month of November, preferably with a mathematical background, I decided to dedicate the month to Emmy Noether because the wordplay worked.

I dream of a balanced life and a puppy. My dream is to have a (permanent!) job that combines research and science communication with equal importance, in a warm and stimulating working environment, and that allows me to have a rich private life.

I put out my idea in Twitter and Katie Steckles, from The Aperiodical, liked it and was very enthusiastic about it. Katie is a mathematician and an experienced maths communicator from the UK and we had met when we were both bloggers at the HLF. We gathered and prepared a list of facts about Emmy Noether’s life, one for each day, and several people joined us in this project. The preparatory phase was a huge success in itself: I read various sources on Emmy Noether and learned many new things about her life and her research, that I wouldn’t have learnt otherwise.

Is there any dream you have?

I dream of a balanced life and a puppy. My dream is to have a (permanent!) job that combines research and science communication with equal importance, in a warm and stimulating working environment, and that allows me to have a rich private life. I want to be able to enjoy my work, and maths is a very social activity, so I dream of having enriching collaborations and good relationships with my colleagues.